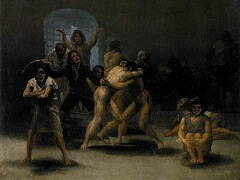

Saturn Devouring his Son, 1820-23 by Francisco Goya

Saturn ate his sons partly because he feared their power when grown men. Goya based this design on a picture by Rubens of the same subject and in seventeenth-century emblem books Saturn signified the weariness of the aged for whom life has become burdensome. Hung in the same room in Goya's house, the 'Quinta del Sordo', Saturn also accompanied a witches' sabbath; Judith and Holofernes, the emblem of the irresistible woman; and a portrait of a girl, thought to be Goya's mistress, Leocadia Weiss, who leans on a tomb and is dressed in mourning. These works, the celebrated 'black paintings', may have been conceived as the artist's testament, a series of ironic reflections on his old age and approaching death. Having moved to the 'Quinta del Sordo' in 1819, Goya carried out a number of improvements on the house and then decorated the two main rooms on the ground floor and first floor with a total of fourteen paintings.

Another painting on the first floor, representing two witches, was by Javier Goya and is now lost. The themes of all these works remain a mystery. While the paintings which were in the lower room seem to express the idea of old age, those on the first floor are almost incomprehensible: they incorporate a depiction of floating black figures, thought by some biographers to be the Fates; the Asmodea; two men sinking in quicksand while beating each other over the head with clubs; two young people mocking an exhibitionist; a religious procession; and a dog half buried in sand. As they are damaged it is impossible to identify any of the subjects with complete assurance, any more than it is possible to be completely certain over their original placing in the house. The scholar Charles Yriarte examined these works in 1867, when they were still in Goya's house, and it is his evidence and that of Goya's pupil and executor, Antonio Brugada, that form the basis for most modern assumptions about the 'black paintings'. Obviously these works were not commissioned, and they may have been only an immense private experiment on Goya's part to bring his style to an almost unprecedented freedom. In December 1825, Goya wrote to a friend in Paris describing forty miniatures which he had apparently painted the previous winter. The subjects of these miniatures are almost identical to those of the 'black paintings': Judith and Holofernes; a number of elderly figures eating, drinking or begging; a monk; a maja; and a man picking fleas from a dog. Although these tiny works in oil on ivory would seem to be quite different from the thick surfaces of Goya's 'black paintings', painted straight onto a plaster wall, the livid, dark colouring and the distorted figures of the miniatures are not unlike those of the works originally in the 'Quinta'. In his letter Goya was enthusiastic about his techniques, saying that the miniatures 'look more like the brush-work of Diego Velazquez than of Mengs'. Although both the miniatures and the 'black paintings' progressed far beyond Velazquez in their style, Goya's remark suggests that for him the importance of this kind of painting lay primarily in the technical challenge it offered. He seems to have attached little importance to such work once it was finished. Only some twenty of the miniatures have come to light, and the 'black paintings' were abandoned by their creator as soon as they were finished: in 1823 Goya gave the 'Quinta' to his grandson Mariano and subsequently left Spain for France. Mariano Goya sold the house in 1859.

In 1873 it was bought by a German banker, Emil Erlanger, who had the 'black paintings' transferred onto canvas and sent them for exhibition in Paris in 1878. They seem to have aroused little interest except for the violent reaction of the English critic P. G. Hamerton, who thought they were immoral. Given to the Prado in 1881, they now rank among Goya's most memorable works.